- Home

- McAllister, Bruce

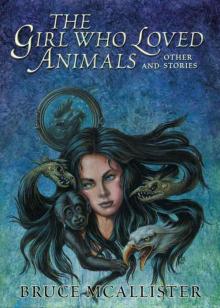

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories Read online

The Girl Who Loved Animals

And Other Stories

Bruce McAllister

With an Introduction by

Harry Harrison

And an Afterword by

Barry N. Malzberg

CEMETERY DANCE PUBLICATIONS

Baltimore MD

2012

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories Copyright © 2007 by Bruce McCallister

A Man of Our Time Copyright © 2007 by Harry Harrison

Afterword: The Arc of Circumstance Copyright © 2007 by Barry N. Malzberg

“Angels,” first published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, May 1990.

“The Ark,” first published in OMNI, September 1985.

“Assassin,” first published in OMNI, February 1994.

“Benji’s Pencil,” first published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, March 1969.

“The Boy in Zaquitos,” first published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, January 2006.

“Dream Baby,” first published in In the Field of Fire, edited by Jack Dann and Jeanne Van Buran Dann, Tor, 1987.

“The Faces Outside,” first published in if: Worlds of Science Fiction, July 1963.

“The Girl Who Loved Animals,” first published in OMNI, May 1988.

“Hero, The Movie,” first published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, July 2005.

“Kin,” first published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, February 2006.

“Little Boy Blue,” first published in OMNI, June 1989.

“The Man Inside,” first published in Galaxy Science Fiction, May 1969.

“Moving On,” first published in OMNI Best Science Fiction Three, edited by Ellen Datlow, OMNI Books, 1993.

“Southpaw,” first published in Asimov’s Science Fiction, August 1993.

“Spell,” first published in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, August 2005.

“Stu,” first published online on SCIFICTION, November 23, 2005.

“World of the Wars,” first published in Mars, We Love You, edited by Jane Hipolito and Willis E. McNelly, Doubleday, 1971.

Edited by Marty Halpern

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Cemetery Dance Publications

132-B Industry Lane, Unit #7

Forest Hill, MD 21050

http://www.cemeterydance.com

First Digital Edition

ISBN-13: 978-1-58767-330-6

Cover Artwork Copyright © 2012 by Jill Bauman

Digital Design by DH Digital Editions

To my wife

Amelie

And to my children

Annie, Ben and Liz

For the love that makes all things possible

Acknowledgements

To my mentors in writing, interdisciplinary scholarship, university life, and life at large—without whom these stories would not have been written and without whom a life would have been lived much less well and wisely: Carl Glick, Harry Harrison, Howard Hurlbut, Willis McNelly, Barry Malzberg, Rebecca Rio-Jelliffe, and Jack Tobin.

To my agent, Russell Galen, the most patient of men.

To my magazine editors—for their generosity of spirit, high standards, and faith: Fred Pohl, Ed Ferman, Terry Carr, Gardner Dozois, Ellen Datlow, Gordon Van Gelder, Gavin Grant, Sheila Williams, Sean Wallace, and Bridget McKenna.

And, finally, to my excellent editor at Golden Gryphon, Marty Halpern; and to the hardcover edition's cover artist, the gifted John Picacio.

Introduction: A Man of Our Time

The year was 1969, and I was living in San Diego in the sunny state of California. I was a hardworking freelancer staying alive by turning out at least a novel a year—and a number of short stories as well. Since at one time I had edited a number of science fiction magazines, I had these editorial talents to fall back on if needs be.

And I needed them. When Joan and I had moved to Europe ten years earlier, our baby, Todd, was just a year old. Living then, while not exactly easy, was certainly easier with the dollar strong and our needs simple. Now with a mortgage, a new car, and daughter Moira happily expanding our family, I needed to turn the handle on the side of the typewriter harder and longer. (I ended up editing fifty anthologies, mostly with Brian Aldiss, but that is another story.) Now I was reading stories for possible use in the Best SF: 1969. The pile of magazines next to my armchair was high and every one had to be gone through carefully.

The top one was an issue of Galaxy; I picked it up with a certain expectation. Fred Pohl was an excellent editor and could be counted upon to have a few interesting stories in every issue.

I had just started reading a story by a writer I had never heard of when Joan called me for dinner. I flipped the page, saw that it was a short-short of under a thousand words. “On the way,” I called out and turned the page. Finished the story with a smile and put a marking slip into the magazine. We could use it.

The story was “The Man Inside,” and the author was the then-unknown Bruce McAllister.

In addition to the slogging work, editing has an unexpected pleasure; you make new friends. Science fiction writers are a gregarious lot. They enjoy meeting each other, at conventions or elsewhere, and a certain amount of drink is liable to be taken. One of the satisfactions of editing is the chance to start correspondence with other SF writers. It is almost a tautology that good writers make good friends. (I can think of only one, perhaps two, exceptions to that rule out of all the hundreds of writers that I have known.) In pre-email days, correspondence by post was very much in order. First you wrote and made an offer for the anthology rights. If this is accepted, the editor then responds with contract forms; then signatures and contracts are exchanged and, occasionally, a request for a rewrite. This all necessitates a certain amount of correspondence which, many times, continues well after the story rights have been bought and paid for. Very often this leads to actual meetings in the flesh and, as I have said, a drink or two.

It was most fortuitous that Bruce lived a few miles away from me. At some point during our correspondence he was invited to drop by the house—and he accepted.

I remember that it was on a weekend and the sun was shining. I answered the door chimes and not only was Bruce there—but so was his father and mother. Unexpected but certainly not unwelcome since he was far younger than I had imagined from our correspondence—just a college kid, and his own car was in the repair shop. I ushered them in. His mother a pleasant woman of about my age. His father gray-haired with a most military bearing.

As well he might have—since he was a captain in the US Navy.

That was the first time that Bruce and I met and certainly was not the last. He was writing more fine SF and happily selling it as well while he attended college.

It was soon after this that I turned to him for aid. What I really needed to help me in my editorial chores was a “first reader.” Each year I had to plow through all the science fiction magazines and anthologies to find the stories for the “year’s best.” To do this I had to read between two hundred and three hundred stories. It was a daunting task since I also had to write a novel—and a few short stories—in the same period. The stack of magazines by my chair seemed to grow not shrink; I was growing desperate. What I needed was that first reader. Someone to cull out the unacceptable, the not-quite-good enough. And most important of all—the possibles.

I asked

Bruce to do the job and he was, understandably, taken aback. I explained that at worst he might fail. But if it worked out he would supply the help I so badly needed.

The story has a most happy ending. He plowed through the mountain of stories and recommended the possibles. I read these and found myself buying one out of the three that he sent on to me. After that, he became managing editor of the “year’s best” and remained so for many years until a stupid publisher, for even stupider reasons, killed the series. We both profited from the relationship in more ways than one. We’ve remained close friends down through the years. I was greatly honored when he was kind enough to ask me to write this introduction to his first collection.

Since that day so many years ago, he has grown into a writer of many strengths. Look at “Dream Baby,” published here. It is a novelette of great depth and warmth and tells us very much about the human condition. It is pure SF, but is as well written and moving as any work of mainstream fiction. This story was the framework on which he built a novel that well deserved its later success.

I read this volume with great pleasure—a pleasure you will surely share. Some of the stories are old friends; others a happy surprise. In all of them you will find a humanity that is all too often missing from SF. At other times there is the chill of disorientation and alienness that only good SF—and good writing—can convey. Read the collection’s title story for a frightening, yet moving look at a possible future.

But as good wine needs no bush, so these stories don’t need my approval.

Thank you, Bruce.

Harry Harrison

Sussex, England

Dream Baby

Dream Baby, got me dreamin’ sweet dreams

The whole day through.

Dream Baby, got me dreamin’ sweet dreams

The night time too.

—Cindy Walker

I don’t know whether I was for or against the war when I went. I joined and became a nurse to help. Isn’t that why everyone becomes a nurse? We’re told it’s a good thing, like being a teacher or a mother. What they don’t tell us is that sometimes you can’t help.

Our principal gets on the PA one day and tells us how all these boys across the country are going over there for us and getting killed or maimed. Then he tells us that Tony Fischetti and this other kid are dead, killed in action, Purple Hearts and everything. A lot of the girls start crying. I’m crying. I call the Army and tell them my grades are pretty good, I want to go to nursing school and then ’Nam. They say fine, they’ll pay for it but I’m obligated if they do. I say it’s what I want. I don’t know if any other girls from school did it. I really didn’t care. I just thought somebody ought to.

I go down and sign up and my dad gets mad. He says I just want to be a whore or a lesbian, because that’s what people will think if I go. I say, “Is that what you and Mom think?” He almost hits me. Parents are like that. What other people think is more important than what they think, but you can’t tell them that.

I never saw a nurse in ’Nam who was a whore and I only saw one or two who might have been butch. But that’s how people thought, back here in the States.

I grew up in Long Beach, California, a sailor town. Sometimes I forget that. Sometimes I forget I wore my hair in a flip and liked miniskirts and black pumps. Sometimes all I can remember is the hospitals.

I got stationed at Cam Ranh Bay, at the 23rd Medevac, for two months, then the 118th Field General in Saigon, then back to the 23rd. They weren’t supposed to move you around like that, but I got moved. That kind of thing happened all the time. Things just weren’t done by the book. At the 23rd we were put in a bunch of huts. It was right by the hospital compound, and we had the Navy on one side of us and the Air Force on the other side. We could hear the mortars all night and the next day we’d get to see what they’d done.

It began to get to me after about a week. That’s all it took. The big medevac choppers would land and the gurneys would come in. We were the ones who tried to keep them alive, and if they didn’t die on us, we’d send them on.

We’d be covered with blood and urine and everything else. We’d have a boy with no arms or no legs, or maybe his legs would be lying beside him on the gurney. We’d have guys with no faces. We’d have stomachs you could hold in your hands. We’d be slapping ringers and plasma into them. We’d have sump pumps going to get the secretions and blood out of them. We’d do this all day, day in and day out.

You’d put them in bags if they didn’t make it. You’d change dressings on stumps, and you had this deal with the corpsmen that every fourth day you’d clean the latrines for them if they’d change the dressings. They knew what it was like.

They’d bring in a boy with beautiful brown eyes and you’d just have a chance to look at him, to get a chest cut-down started for a subclavian catheter. He’d say, “Ma’am, am I all right?” and in forty seconds he’d be gone. He’d say, “Oh, no,” and he’d be gone. His blood would pool on the gurney right through the packs. Some wounds are so bad you can’t even plug them. The person just drains away.

You wanted to help but you couldn’t. All you could do was watch.

When the dreams started, I thought I was going crazy. It was about the fourth week and I couldn’t sleep. I’d close my eyes and think of trip wires. I’d think my bras and everything else had trip wires. I’d be on the john and hear a sound and think that someone was trip-wiring the latch so I’d lose my hands and face when I tried to leave.

I’d dream about wounds, different kinds, and then the next day there would be the wounds I’d dreamed about. I thought it was just coincidence. I’d seen a lot of wounds by then. Everyone was having nightmares. I’d dream about a sucking chest wound and a guy trying to scream, though he couldn’t, and the next day I’d have to suck out a chest and listen to a guy try to scream. I didn’t think much about it. I couldn’t sleep. That was the important thing. I knew I was going to go crazy if I couldn’t sleep.

Sometimes the dreams would have all the details. They’d bring in a guy that looked like someone had taken an ice pick to his arms. His arms looked like frankfurters with holes punched in them. That’s what shrapnel looks like. You puff up and the bleeding stops. We all knew he was going to die. You can’t live through something like that. The system won’t take it. He knew he was going to die, but he wasn’t making a sound. His face had little holes in it, around his cheeks, and it looked like a catcher’s mitt. He had the most beautiful blue eyes, like glass. You know, like that dog, the weimar-something. I’d start shaking because he was in one of my dreams—those holes and his face and eyes. I’d shake for hours, but you couldn’t tell anybody about dreams like that.

The guy would die. There wasn’t anything I could do.

I didn’t understand it. I didn’t see a reason for the dreams. They just made it worse.

It got so I didn’t want to go to sleep because I didn’t want to have them. I didn’t want to wake up and have to worry about the dreams all day, wondering if they were going to happen. I didn’t want to have to shake all day, wondering.

I’d have this dream about a kid with a bad head wound and a phone call, and the next day they’d wheel in some kid who’d lost a lot of skull and brain and scalp, and the underlying brain would be infected. Then the word would get around that his father, who was a full-bird colonel stationed in Okie, had called and the kid’s mother and father would be coming to see him. We all hoped he died before they got there, and he did.

I’d had a dream about him. I’d even dreamed that we wanted him to die before his mom and dad got there, and he did, in the dream he did.

When he died I started screaming and this corpsman who’d been around for a week or two took me by the arm and got me to the john. I’d gotten sick but he held me like my mom would have and all I could do was think what a mess I was, how could he hold me when I was such a mess? I started crying and couldn’t stop. I knew everyone thought I was crazy, but I couldn’t stop.

Af

ter that things got worse. I’d see more than just a face or the wounds. I’d see where the guy lived, where his hometown was, and who was going to cry for him if he died. I didn’t understand it at first—I didn’t even know it was happening. I’d just get pictures, like before, in the dream and they’d bring this guy in the next day or the day after that, and if he could talk, I’d find out that what I’d seen was true. This guy would be dying and not saying a thing and I’d remember him from the dream and I’d say, “You look like a Georgia boy to me.” If the morphine was working and he could talk, he’d say, “Who told you that, Lieutenant? All us brothers ain’t from Georgia.”

I’d make up something, like his voice or a good guess, and if I’d seen other things in the dream—like his girl or wife or mother—I’d tell him about those, too. He wouldn’t ask how I knew because it didn’t matter. How could it matter? He knew he was dying. They always know. I’d talk to him like I’d known him my whole life and he’d be gone in an hour, or by morning.

I had this dream about a commando type, dressed in tiger cammies, nobody saying a thing about him in the compound—spook stuff, Ibex, MAC SOG, something like that—and I could see his girlfriend in Australia. She had hair just like mine and her eyes were a little like mine and she loved him. She was going out with another guy that night, but she loved him, I could tell. In the dream they brought him into ER with the bottom half of him blown away.

The next morning, first thing, they wheeled this guy in and it was the dream all over again. He was blown apart from the waist down. He was delirious and trying to talk but his jaw wouldn’t work. He had tiger cammies on and we cut them off. I was the one who got him and everyone knew he wasn’t going to make it. As soon as I saw him I started shaking. I didn’t want to see him, I didn’t want to look at him. You really don’t know what it’s like, seeing someone like that and knowing. I didn’t want him to die. I never wanted any of them to die.

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories