- Home

- McAllister, Bruce

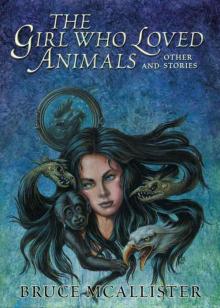

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories Page 3

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories Read online

Page 3

I get up, dreading it. I know he’s not talking about Steve.

They’ve got all the bunkers dug and he takes me to what has to be the CP. There isn’t a guy inside who isn’t in real clean fatigues. There are three or four guys who have the same look this guy has—MDs that don’t ever get their hands dirty—and intel types pointing at maps and pushing things around on a couple of sand-table mock-ups. There’s this one guy with his back turned and everyone else keeps checking in with him.

He’s tall. He’s got a full head of hair but it’s going gray. He doesn’t even have to turn around and I know.

It’s the guy in civvies at the end of the hallway at the 23rd, the guy that walked away with Steve on Phan Hao Street.

He turns around and I don’t give him eye contact. He looks at me, smiles, and starts over. There are two guys trailing him and he’s got this smile that’s supposed to be charming.

“How are you feeling, Lieutenant?” he says.

“Everybody keeps asking me that,” I say, and I wonder why I’m being so brave.

“That’s because we’re interested in you, Lieutenant,” he says. He’s got this jungle outfit on with gorgeous creases and some canvas jungle boots that breathe nicely. He looks like an ad from a catalog but I know he’s no joke, he’s no pogue lifer. He’s wearing this stuff because he likes it, that’s all. He could wear anything he wanted to because he’s not military, but he’s the CO of this operation, which means he’s fighting a war I don’t know a thing about.

He tells me he’s got some things to straighten out first, but that if I go back to my little bunker he’ll be there in an hour. He asks me if I want anything to eat. When I say sure, he tells the MD type to get me something from the mess.

I go back. I wait. When he comes, he’s got a file in his hand and there’s a young guy with him who’s got a cold six-pack of Coke in his hand. I can tell they’re cold because the cans are sweating. I can’t believe it. We’re out here in the middle of nowhere, we’re probably not even supposed to be here, and they’re bringing me cold Coke.

When the young guy leaves, the CO sits on the edge of the cot and I sit on the other and he says, “Would you like one, Lieutenant?”

I say, “Yes, sir,” and he pops the top with a church key. He doesn’t take one himself and suddenly I wish I hadn’t said yes. I’m thinking of old movies where Jap officers offer their prisoners a cigarette so they’ll owe them one. There’s not even any place to put the can down, so I hold it between my hands.

“I’m not sure where to begin, Lieutenant,” he says, “but let me assure you you’re here because you belong here.” He says it gently, real softly, but it gives me a funny feeling. “You’re an officer and you’ve been in-country for some time. I don’t need to tell you that we’re a very special kind of operation here. What I do need to tell you is that you’re one of three hundred we’ve identified so far in this war. Do you understand?”

I say, “No, sir.”

“I think you do, but you’re not sure, right? You’ve accepted your difference—your gift, your curse, your talent, whatever you would like to call it but you can’t as easily accept the fact that so many others might have the same thing, am I right, Mary—may I call you Mary?”

I don’t like the way he says it but I say yes.

“We’ve identified three hundred like you, Mary. That’s what I’m saying.”

I stare at him. I don’t know whether to believe him.

“I’m only sorry, Mary, that you came to our attention so late. Being alone with a gift like yours isn’t easy, I’m sure, and finding a community of those who share it—the same gift, the same curse—is essential if the problems that always accompany it are to be worked out successfully, am I correct?”

“Yes.”

“We might have lost you, Mary, if Lieutenant Balsam hadn’t found you. He almost didn’t make the trip, for reasons that will be obvious later. If he hadn’t met you, Mary, I’m afraid your hospital would have sent you back to the States for drug abuse if not for what they perceived as an increasingly dysfunctional neurosis. Does this surprise you?”

I say it doesn’t.

“I didn’t think so. You’re a smart girl, Mary.”

The voice is gentle, but it’s not.

He waits and I don’t know what he’s waiting for.

I say, “Thank you for whatever it was that—”

“No need to thank us, Mary. Were that particular drug available back home right now, it wouldn’t seem like such a gift, would it?”

He’s right. He’s the kind who’s always right and I don’t like the feeling.

“Anyway, thanks,” I say. I’m wondering where Steve is.

“You’re probably wondering where Lieutenant Balsam is, Mary.”

I don’t bother to nod this time.

“He’ll be back in a few days. We have a policy here of not discussing missions—even in the ranks—and as commanding officer I like to set a good example. You can understand, I’m sure.” He smiles again and for the first time I see the crow’s-feet around his eyes, and how straight his teeth are, and how there are little capillaries broken on his cheeks.

He looks at the Coke in my hands and smiles. Then he opens the file he has. “If we were doing this the right way, Mary, we would get together in a nice air-conditioned building back in the States and go over all of this together, but we’re not in any position to do that, are we?

“I don’t know how much you’ve gathered about your gift, Mary, but people who study such things have their own way of talking. They would call yours a ‘TPC hybrid with traumatic neurosis, dissociative features.’ ” He smiles. “That’s not as bad as it sounds. It’s quite normal. The human psyche always responds to special gifts like yours, and neurosis is simply a mechanism for doing just that. We wouldn’t be human if it didn’t, would we?”

“No, we wouldn’t.”

He’s smiling at me and I know what he wants me to feel. I feel like a little girl sitting on a chair, being good, listening, and liking it, and that is what he wants.

“Those same people, Mary, would call your dreams ‘spontaneous anecdotal material’ and your talent a ‘REM-state precognition or clairvoyance.’ They’re not very helpful words. They’re the words of people who’ve never experienced it themselves. Only you, Mary, know what it really feels like inside. Am I right?”

I remember liking how that felt—only you. I needed to feel that, and he knew I needed to.

“Not all three hundred are dreamers like you, of course. Some are what those same people would call ‘kinetic phenomena generators.’ Some are ‘tactility-triggered remoters’ or ‘OBE clears.’ Some leave their bodies in a firefight and acquire information that could not be acquired in ordinary ways, which tells us that their talent is indeed authentic. Others see auras when their comrades are about to die, and if they can get those auras to disappear, their friends will live. Others experience only a vague visceral sensation, a gut feeling which tells them where mines and trip wires are. They know, for example, when a crossbow trap will fire and this allows them to knock away the arrows before they can hurt them. Still others receive pictures, like waking dreams, of what will happen in the next minute, hour, or day in combat.

“With very few exceptions, Mary, none of these individuals experienced anything like this as civilians. These episodes are the consequence of combat, of the metabolic and psychological anomalies which life-and-death conditions seem to generate.”

He looks at me and his voice changes now, as if on cue. He wants me to feel what he is feeling, and I do, I do. I can’t look away from him and I know this is why he is the CO.

“It is almost impossible to reproduce them in a laboratory, Mary, and so these remarkable talents remain mere anecdotes, events that happen once or twice within a lifetime—to a brother, a mother, a friend, a fellow soldier in a war. A boy is killed on Kwajalein in 1944. That same night his mother dreams of his death. She has never before dreamed su

ch a dream, and the dream is too accurate to be mere coincidence. He dies. She never has a dream like it again. A reporter for a major newspaper looks out the terminal window at the Boeing 707 he is about to board. He has flown a hundred times before, enjoys air travel, and has no reason to be anxious today. As he looks through the window the plane explodes before his very eyes. He can hear the sound ringing in his ears and the sirens rising in the distance; he can feel the heat of the ignited fuel on his face. Then he blinks. The jet is as it was before—no fire, no sirens, no explosion. He is shaking—he has never experienced anything like this in his life. He does not board the plane, and the next day he hears that its fuel tanks exploded, on the ground, in another city, killing ninety. The man never has such a vision again. He enjoys air travel in the months, and years, ahead, and will die of cardiac arrest on a tennis court twenty years later. You can see the difficulty we have, Mary.”

“Yes,” I say quietly, moved by what he’s said.

“But our difficulty doesn’t mean that your dreams are any less real, Mary. It doesn’t mean that what you and the three hundred like you in this small theater of war are experiencing isn’t real.”

“Yes,” I say.

He gets up.

“I am going to have one of my colleagues interview you, if that’s all right. He will ask you questions about your dreams and he will record what you say. The tapes will remain in my care, so there isn’t any need to worry, Mary.”

I nod.

“I hope that you will view your stay here as deserved R & R, and as a chance to make contact with others who understand what it is like. For paperwork’s sake, I’ve assigned you to Golf Team. You met three of its members on your flight in, I believe. You may write to your parents as long as you make reference to a medevac unit in Pleiku rather than to our actual operation here. Is that clear?”

He smiles like a friend would, and makes his voice as gentle as he can. “I’m going to leave the rest of the Coke. And a church key. Do I have your permission?” He grins. It’s a joke, I realize. I’m supposed to smile. When I do, he smiles back and I know he knows everything, he knows himself, he knows me, what I think of him, what I’ve been thinking every minute he’s been here.

It scares me that he knows.

His name is Bucannon.

The man that came was one of the other MD types from the tent. He asked and I answered. The question that took the longest was “What were your dreams like? Be as specific as possible both about the dream content and its relationship to reality—that is, how accurate the dream was as a predictor of what happened. Describe how the dreams and their relationship to reality (i.e., their accuracy) affected you both psychologically and physically (e.g., sleeplessness, nightmares, inability to concentrate, anxiety, depression, uncontrollable rages, suicidal thoughts, drug abuse).”

It took us six hours and six tapes.

We finished after dark.

I did what I was supposed to do. I hung around Golf Team. There were six guys, this lieutenant named Pagano, who was in charge, and this demo sergeant named Christabel, who was their “talent.” He was, I found out, an “OBE clairvoyant with EEG anomalies,” which meant that in a firefight he could leave his body just like Steve could. He could leave his body, look back at himself—that’s what it felt like—and see how everyone else was doing and maybe save someone’s ass. They were a good team. They hadn’t lost anybody yet, and they loved to tease this sergeant every chance they got.

We talked about Saigon and what you could get on the black market. We talked about missions, even though we weren’t supposed to. The three guys from the slick even got me to talk about the dreams, I was feeling that good, and when I heard they were going out on another mission at 0300 hours the next morning, without the sergeant—some little mission they didn’t need him on—I didn’t think anything about it.

I woke up in my bunker that night screaming because two of the guys from the slick were dead. I saw them dying out in the jungle, I saw how they died, and suddenly I knew what it was all about, why Bucannon wanted me here.

He came by the bunker at first light. I was still crying. He knelt down beside me and put his hand on my forehead. He made his voice gentle. He said, “What was your dream about, Mary?”

I wouldn’t tell him. “You’ve got to call them back,” I said.

“I can’t, Mary,” he said. “We’ve lost contact.”

He was lying I found out later: he could have called them back—no one was dead yet—but I didn’t know that then. So I went ahead and told him about the two I’d dreamed about, the one from Mississippi and the one who’d thought I was a Donut Dolly. He took notes. I was a mess, crying and sweaty, and he pushed the hair away from my forehead and said he would do what he could.

I didn’t want him to touch me, but I didn’t stop him. I didn’t stop him.

I didn’t leave the bunker for a long time. I couldn’t.

No one told me the two guys were dead. No one had to. It was the right kind of dream, just like before. But this time I’d known them. I’d met them. I’d laughed with them in the daylight and when they died I wasn’t there, it wasn’t on some gurney in a room somewhere. It was different.

It was starting up again, I told myself.

I didn’t get out of the cot until noon. I was thinking about needles, that was all.

He comes by again at about 1900 hours, just walks in and says, “Why don’t you have some dinner, Mary. You must be hungry.”

I go to the mess they’ve thrown together in one of the big bunkers. I think the guys are going to know about the screaming, but all they do is look at me like I’m the only woman in the camp, that’s all, and that’s okay.

Suddenly I see Steve. He’s sitting with three other guys and I get this feeling he doesn’t want to see me, that if he did he’d have come looking for me already, and I should turn around and leave. But one of the guys is saying something to him and Steve is turning and I know I’m wrong. He’s been waiting for me. He’s wearing cammies and they’re dirty—he hasn’t been back long—and I can tell by the way he gets up and comes toward me he wants to see me.

We go outside and stand where no one can hear us. He says, “Jesus, I’m sorry.” I’m not sure what he means.

“Are you okay?” I say, but he doesn’t answer.

He’s saying, “I wasn’t the one who told him about the dreams, Mary, I swear it. All I did was ask for a couple hours layover to see you, but he doesn’t like that—he doesn’t like ‘variables.’ When he gets me back to camp, he has you checked out. The hospital says something about dreams and how crazy you’re acting, and he puts it together. He’s smart, Mary. He’s real smart—”

I tell him to shut up, it isn’t his fault, and I’d rather be here than back in the States in some VA program or ward. But he’s not listening. “He’s got you here for a reason, Mary. He’s got all of us here for a reason and if I hadn’t asked for those hours he wouldn’t know you existed—”

I get mad. I tell him I don’t want to hear any more about it, it isn’t his fault.

“Okay,” he says finally. “Okay.” He gives me a smile because he knows I want it. “Want to meet the guys on the team?” he says. “We just got extracted—”

I say sure. We go back in. He gets me some food and then introduces me. They’re dirty and tired but they’re not complaining. They’re still too high off the mission to eat and won’t crash for another couple of hours yet. There’s an SF medic with the team, and two Navy SEALs because there’s a riverine aspect to the mission, and a guy named Moburg, a Marine sniper out of Quantico. Steve’s their CO and all I can think about is how young he is. They’re all so young.

It turns out Moburg’s a talent, too, but it’s “anticipatory subliminal”—it only helps him target hits and doesn’t help anyone else much. But he’s a damn good sniper because of it, they tell me.

The guys give me food from their trays and for the first time that day I’m feeling hungry. I’m ea

ting with guys that are real and alive and I’m really hungry.

Then I notice Steve isn’t talking. He’s got that same look on his face. I turn around.

Bucannon’s in the doorway, looking at us. The other guys haven’t seen him, they’re still talking and laughing—being raunchy.

Bucannon is looking at us and he’s smiling, and I get a chill down my spine like cold water because I know—all of a sudden I know—why I’m sitting here, who wants it this way.

I get up fast. Steve doesn’t understand. He says something. I don’t answer him, I don’t even hear him. I keep going. He’s behind me and he wants to know if I’m feeling okay, but I don’t want to look back at him, I don’t want to look at any of the guys with him, because that’s what Bucannon wants.

He’s going to send them out again, I tell myself. They just got back, they’re tired, and he’s going to send them out again, so I can dream about them.

I’m not going to go to sleep, I tell myself. I walk the perimeter until they tell me I can’t do that anymore, it’s too dangerous. Steve follows me and I start screaming at him, but I’m not making any sense. He watches me for a while and then someone comes to get him, and I know he’s being told he’s got to take his team out again. I ask for some Benzedrine from the Green Beanie medic who brings me aspirin when I want it but he says he can’t, that word has come down that he can’t. I try writing a letter to my parents but it’s 0400 hours and I’m going crazy trying to stay awake because I haven’t had more than four hours’ sleep for a couple of nights and my body temperature’s dropping on the diurnal.

I ask for some beer and they get it for me. I ask for some scotch. They give it to me and I think I’ve won. I never go to sleep on booze, but Bucannon doesn’t know that. I’ll stay awake and I won’t dream.

But it knocks me out like a light, and I have a dream. One of the guys at the table, one of the two SEALs, is floating down a river. The blood is like a woman’s hair streaming out from his head. I don’t dream about Steve, just about this SEAL who’s floating down a river. It’s early in the mission. Somehow I know that.

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories

The Girl Who Loved Animals and Other Stories